The connection between negative emotion and conflict is clear.1 And yet it is also well known how positive emotion reduces conflict and maintains marriage.2 Furthermore, positive emotion (which is friendship) is additive over time and with the incidence of frequent positive experiences, which is to say that friendship within marriage needs to be invested in, and maintained. 3

We have also spent a great deal of time in this body of work, describing the importance of time and timing in a relationship going well.4

Beyond timing, there also needs to be a degree of "bonding" that has occurred between partners, which is the same thing we have been referring to when we say that friendship has four components, similar to that described by Aristotle.5 We might, then, survive as a couple based on the sheer effort made at being happy in the presence of the other person, consistently.6

Attachment and bonding have been described in Romantic Dynamics as "imprinting" processes - automatic behaviors in all human beings that are best known to occur in infancy and early childhood, and in which a child instinctually latches onto a mother or father with intense desire and need. It took until the past two decades of research to come to the conclusion that attachment also pertains to the style with which adults fall in love and connect instinctually. 7

As you might guess, attachment, as a "survival level" process, can produce intense feelings and even trauma when there is loss, such as in a breakup or divorce, or the threat of them. This originally was studied in infancy and childhood as it pertains to our parents.8 Yet, even while attachment and loss were originally studied in terms of infancy, what we know now about adult romantic connections and the predictors of the demise of a relationship - such as in the work of Dr. John Gottman - the emotional stakes of a breakup or divorce may feel at the instinctual, unconscious level as no less severe than a threat to life itself, such as seen suffered by infants in orphanages.9

One major lesson that we have learned in seeing romance have three phases is that the emotions shared by a couple are paramount, whatever their intellectual differences. 10 When there is so much at stake about the emotional connection, couples can't afford to let one or the other person's stress, anxiety or anger get in the way.11 In fact, we can't begin to partner toward goals as a couple until we have learned to read each other"s emotional needs as teammates.12

Throughout Romantic Dynamics, we must wrestle with the differences in characteristics between romantic factors dictated by the polling data of sociology as a "social science," and the facts and repeatable, reliable and enduring principles of biology as a "hard science."13

To this end, there is a prime importance to linguistics and the words we choose in order to describe what we feel and experience as men and women. This can mean a successful relationship if we choose to describe ourselves accurately, and failure if we don't.14 The notion of language and its accuracy in describing the vague, the invisible, and even the unconscious, unknowable aspects of our minds is an interesting challenge, yet there is a model to use in doing so.15

At some point in our development, we did have a kind of understanding of what we were perceiving, and yet had no words to describe it yet. In our very early years, at some poinr, we were "preverbal," and yet what we were experiencing was very real.16 Sometimes, language even seduces us into having sentimentality that we should not, and our imaginations can cause us to make romantic decisions not in our best insterest.17

To this end, we need tools and methods for decoding language (or its lack) in order to accurately understand romance, and in order to make wise decisions about it.18We are not fated to have the love which the world serves up to us, randomly. Rather, we can educate ourselves to better relationships.19

We can change ourselves, no matter what we have experienced before.20 We can alter the course of our lives and loves.21 We can learn to trust even after trust is broken.22 As w trust more, in more confidence, we can also become more empathic partners.23

We are more flexible and adaptable in romance than one might think, which makes biological sense if we consider the highly unlikely chances of living most of our lives in an approximately five square mile radius of several thousand, or tens of thousands of people at best, with limited time to meet mates after earning our day's keep, and planning how to work for the next day's keep. This ability began when we were small, and hopefully, as it pertains to romantic potential, never completely goes away. 24

In Romantic Dynamics, we learn that there are three phases of human courtship - the sexual attraction, the emotional attraction, and the intellectual attraction. Desire, friendship/love, and then commitment, we telescope out for inspection, step by step. Truth be told, however, and we must admit that these three all begin developing upon first meeting a person of potential, although at very different rates. We separate them out so that we can see them operating separately, even if they operate simultaneously by the time we call ourselves, "a couple."

We can see the three phases simultaneously, but when we examine each feature of them, one by one, in each facet we ought to be considering the research backing behind the concept.

SEXUAL ATTRACTION

There is a great deal of conflict going on, not only in our individual relationships, but between the genders in our society in general. Our approach in Romantic Dynamics will not be to stir up such conflict in the form of blaming men for this, or women for that - for our personal, individual failures - but an assumption that people are indeed, attracted to each other, like each other, need each other - that it is the polarity between them - the differences - that attract. Further, we see such psychological principles as "masculinity" and "femininity" to have biological roots, not merely being swayed by sociological observations, public policy, or simply, opinion polls.

When we leave sociological aspects, interspersed among the biological forces at work, romantic attraction remains remarkably complex.25 In this unconscious, nonverbal arena of behavior, it is often difficult to even find language to describe what is going on, and we may tend to use words like, "attraction" and "attracted," to denote any manner of being drawn to another person, from only meaning, "desire," to meaning that we have intellectual curiosity about the mind of another person, or friendship shared with them, all the way to "attraction" actually being a synonym for all aspects of love and romance.26

Sexual Attraction and attraction to another person in general has been said to be multivariate, which is to say that numerous things about another person attract us to them. In Romantic Dynamics, we believe that we have come close to categorizing and deconstructing the most important and effective variables, and connected them in a framework that will make logical and practical sense to you, a different experience from the hodge-podge of blogs, research, gossip columns and other sources that you may have been confused by in the past.27

To those ends, we will look at femininity and masculinity as forces in our psychology which operate by certain rules or processes that are repeatable and reliable, across all cultures and demographics, and indeed, across all human history. This is not to leave out those with sexual preferences not in the majority, but yet another reflection of polarity and differences between two partners which bring them together in attraction.

Masculinity will then have certain repeatable, reliable functions and characteristics. 28 As will femininity. Both of these exist at the "identity level" of a person, and at the same time, constitute automatic, unconscious processes, different from the other, and yet complementary to the other, even encouraging the growth and expression in the other, of what we call, "gender instincts."

Masculinity and femininity are then, sets of instincts, unconscious, coded instructions for automatic behaviors, likely written out at least in some partial fashion, in the X and Y chromosomes, respectively.

Meanwhile, our formative years also have a lasting effect on our future romantic behavior, by way of our interactions with our own same-sex and opposite-sex parents. Our gender identity does not exist in a vacuum, rendering us the same as every other person with the same gender identity. It is affected by the events, interactions, and what we will learn to be called, "imprinting processes" that include attachment, bonding, identification and initiation. These are common to all human beings as processes, and yet, because of the nature of the specifics of the events and people involved, prove our specific romantic stories to be very unique and individual to us. Which you may find to be quite relieving and empowering.29

In fact, the imprinted processes such as attachment have not been intensively studied beyond the childhood years, into adulthood and applied to adult romantic relationships - until the past two decades. 30

We will learn of the usefulness of defining words that pertain to our psychology in a way that is very precise and practical. For example, the usefulness of the synonyms, "desire," "sexual attraction," "survival," "passion," and their connection to the synonyms, "instinct," "unconscious," and "primitive" behavior such as those that can occur around the topic of sex and sexual behavior. All humans feel these feelings and have these behaviors, which may or may not lead to friendship or love, let alone a stable partnership, yet they can and do lead to attachment to each other in adult life.31 This is a stabilizing force for an individual or the couple, in a world of social and psychological danger and loneliness.

We become "attached" to our parents and form a bond with them, then later in life, as adults, we "attach" to those with similar traits and features as our opposite sex parent (observed by Freud, in the "Oedipus" complex), yet we are also largely unconscious of our own instinctual behaviors which will bear out in us having at least some traits and behaviors similar to our own same sex parent.32

One way of describing "masculinity" or "femininity" in behavior in a way that is uniform and repeatable, is to see masculine instincts as those universal behaviors among men which lead males to feel that term, "passion" (for life, and or for a partner.) Likewise, "femininity" is a set of universal instincts among women which leads them to feel more passion for life and or for a partner.33

This concept will be crucial for singles to understand, but then again, sexuality is a large part of marriage as well.34 In doubling back to the beginning of our courtship sequence, married couples will find themselves having to do just as much work at understanding the instincts of the other gender as they did when they were single, and just as attached, thrilled and frustrated at once, with the "parent" they never saw themselves being attracted to in adult life, and becoming the "parent" that they swore they would never share similarities with, in adult, romantic life.35

In today's world of such universal conflict between the genders, it iwll become ever more challenging to find common language with the opposite sex, let alone language which to them feels appealing and alluring.36

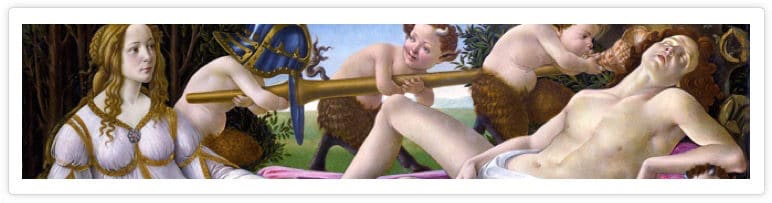

Step one of all courtship, and of sexual attraction, "Boy Meets Girl," - Beauty and Mystery - is nonverbal, and wordless. For the male, with the masculine sensibilities of Ares from the ancient Greek pantheon, the Aphrodite-like beauty of the woman in his eyes will be the first attractor. The way she moves, and the look in her eye, the physical cues she gives unconsciously and automatically draw him in.

In parallel, the woman, with the feminine sensibilities of Psyche to her Eros, will be drawn to the mysteriousness of his behavior, his "aura," his "mystique." It will be his Hermes instinct to be mysterious as a single man can do, or the secretive ways of Eros to his bride, Psyche, that is the mysterious way of the married man. If he manages to avoid the gossipy plague of the "Sisters of Psyche" whom we learn about, he will be discovered by her to be a "god," not a "monster."

It will become apparent to many that there is a "right answer" and "wrong answer" in the words we choose to communicate with in appealing to the other gender. 37

In a conflict-ridden relationship between men and women, en masse, you may find it frustrating enough that we can no longer choose words which will satisfy so many requirements - that we be true to ourselves, within our gender identity, that we express our interest in another person, that the words we choose, appeal, not offend, and that these word be understood in a way which makes the other person feel good about themselves and their life, as opposed to feeling defensive or misunderstood.38

Step two of sexual attraction - "Ladies and Gentlemen" - will see us moving into nonverbal, physical behavior that is kind and tender, and even parental in nature. We touch for the first time and reach some small amount of physical intimacy, driven by the instincts of the figures Zeus for the man, and Hera for the woman - the "mother" and "father" instincts which bring alive the old attachments that we long ago made with our opposite-sex parents.

It is the step at which we start to call each other by cute nicknames such as, "baby," which literally resembles the parent-child desire we once had. It is also a preview of how we will be treated when we weaken and need a partner to lift us, or when our partner becomes a source of happiness through allowing us the chance to help them in return.

Desire has been growing, and physical intimacy escalates, but only to a point, where the brakes are put on, and a standing back to re-evaluate the growing passion occurs. It is here that the woman must do a thorough preview of the man's character, of his behavior should she allow him to become a partner someday, and where the man is given the chance to feel even more passionate and special in her eyes, by passing her 'tests of masculinity' and 'tests of character.'

How much more so is it true that in order to reach a full, sexual desire, to fall in love and eventually find ourselves passing all the tests which lead to friendship, partnership and romantic longevity, that we must realize at some point there must be physical touch. If we are to get to physical intimacy, we must at some point, reach an intersection of physical desire and emotional trust, at intellectual respect and raw, animalistic desire. We must learn to know when it is okay to touch courteously at first, and later with passion and ever greater physical intimacy.39

If the man passes the tests he is unconsciously given, he will feel all the more valuable to her, and to himself, and excited to be with her, potentially to commence a deep friendship in the next phase. She too, will feel content with his qualities, that she would befriend him whether or not they were romantically involved, because he meets the standards for friendship in a way that satisfies her as well.

EMOTIONAL ATTRACTION

If attachment is one of the unconscious, "imprinted" processes, and is reinvigorated by meeting a new person for whom we initially develop sexual attraction, then we can also consider many of the workings of the sexual attraction phase of courtship to be unconscious, automatic, instinct-based, and pertaining to the body, actions, and all that is nonverbal.

However, once we move into the area of emotions, "bonding" and friendship, that term, "bonding" - as in a "friendship bond" or "love bond" - starts to have a cross-over meaning in carrying us from the pure, unconscious instincts, into the subconscious emotions that have the potential to be made fully conscious, and have meaning. We may eventually say the phrase, "I love you," then stop to think about that and what it means in terms of defining our relationship more formally. We are no longer unconsciously drawn to desiring another person, but instead, find ourselves also awake and aware of a love and friendship that is developing.

Left to itself, desiring, attaching to, and being sexually attracted to a person as an experience can pull us in all kinds of illogical and dramatic directions. By contrast, the emotions are slower to build and serve us, providing more stable ground to walk on in our relationships, and bouying the intense feelings of attachment.40

It is our aim, in Romantic Dynamics, to take what has been elucidated by the research, and render it in normal language that anyone can understand, and more importantly, implement. As such, for us to move into phase two of courtship, and the emotional attraction, friendship and love that exist there, you will start to notice that we move from behaviors and romantic experiences for which there are no words - it is nonverbal/preverbal - to there being common, everyday words for what we are experiencing. The world of the emotions bridges the gap between what is non-verbal or physical in expression, and what is purely intellectual, logical and clear, when we pay attention using the conscious mind.41

The most logical place to start, in the first step of emotional attraction (step four of courtship overall) - Finding Value in Each Other - makes sense. "Value" is one of the many synonyms for love, friendship, self-esteem and happiness. We value a possession, a concept or a person to the exact degree that they make us happy. And so this first step of emotional attraction sees us noticing the bump of happiness or friendship that we get in being around another person. We then, value them.

It is even suspected by psychologists, that two interdependent people will literally shape each other's psychology. The Michelangelo phenomenon is a phenomenon observed by psychologists in which interdependent individuals influence and "sculpt" each other (opposite of Blueberry phenomenon, in which interdependent individuals bring out the worst qualities in each other).42

We discover that love, friendship, self-esteem, value, and other synonyms for the positive version of emotions that we encounter in this phase, all simply mean, "happiness."43 Love is simply a shared experience of mutual happiness when we sort out other features of romance, such as the sexuality of phase one and the partnership of phase three.

In seeing self-esteem and happiness as equivalents to love, and to how much we value another person and are valued, we can actually start to codify a language of love in which we can analyze, weigh and measure our progress, and the qualities of our romance.44

In phase two, the emotional attraction, we learn that in the Romantic Dynamics model, self-esteem comes in two varieties that we define as "well-being" and "confidence." That both are necessary for a healthy love relationship (and for healthy parenting." This love and friendship, the mutual elevation of each other's self-esteem, only adds to the preexisting passion and desire that we feel for each other, and in a way supported by neuroscience research.45

Well-being is most similar to having "maternal emotion" or "maternal energy" to provide to ourselves and to others. Since we all occasionally lean on each other emotionally, in parental-dependent ways in a romance, then even in the "unconditional love" of parenting, there is still an ebb and flow of what we provide to each other. If well-being is an emotional sense of satisfaction, or "getting our needs met," then what we "owe" the person who has provided it to us, is "gratitude."46

We then "mother ourselves" when we are assertive enough to go get our own needs met as individuals, and we are "mothering" others when we fulfill the needs of others. There is no better an environment to do this loving action than mutually, with a partner in a romance.47

Synonyms (and confusion) may still abound, if we don't get precise in defining our terms. For example, in Romantic Dynamics, we intend that "gratitude" be an expression of thanks to someone whom has met our needs, while "satisfaction" is more similar to a direct measure of how much well-being we feel or possess. 48 You must certainly know people who have gotten their needs met, and still don't express gratitude in proportion to it. In our lexicon, we tend to refer to this state of a person being one of "pathological narcissism."

It's one of the useful features of separating out the emotional functions of phase two, from the conscious, intellectual and personal growth functions of phase three, and partnership. This is because the emotions may function in romance in a certain way for someone of low maturity level, and the same emotional processes may behave very differently for someone else of high maturity level.49

We will also need to separate out the difference between material or career accomplishment, and that of maturity level in their effects on friendship, happiness and love.50

To be sure, an operative principle of seeing emotions as squarely sitting between the purely unconscious processes of attachment, desire and passion on the one side, and the purely conscious, rational decisions about when, how and with whom to partner for success in romance, the emotions can serve us as a guide as to what to change about ourselves.51 We can pull meaning from the emotions, and then we may "know what to do" in our relationships.52

The more emotionally aware we may become of ourselves, the more emotionally "attuned" in empathy we may become to a partner, and in their eyes, become a better partner.53

You may be wondering, "What about the other variety of self-esteem?" That was the emotional state that in Romantic Dynamics, we call, "confidence." Most literature surrounding this term, when it is used at all, tends to not refer to it by our definition: "The emotional capacity to tolerate risk, change, uncertainty or loss." Instead, its absence tends to be referred to, using the general term, "stress," and well-being used as a synonym for both varieties of self-esteem54

In Romantic Dynamics, we see confidence as a different state and function from well-being, even though we see both as composing our overall self-esteem.

While the endpoint of building well-being ought to lead to an inner sense of satisfaction in ourselves and gratitude toward others for being provided it, confidence ought to instead, lead to an inner sense of safety and peace in ourselves, and something perhaps unexpected toward others, which is "celebration."

You may notice that gratitude is something that we often register toward a specific, individual person, while celebration is something that we most often think of as shared with groups of others. Yet this may make sense to you in seeing that which is "maternal," implying personal intimacy with one person (as in an infant with mother), while that which is "paternal" may be seen as the encouragement to reach out into the vast social world around us, to discover ourselves, our skills and our power among the many.55

This is not gender-specific to refer to the "maternal" or "paternal," but merely a way of referring to that which is interiorly satisfying, as in feeding one's hunger, versus that which reaches out into the world around us, to take the actions which provide security, safety, peace and certainty, to face fears and defeat them, which is the same as the concept and state that we call, "courage."

A male may be maternal or paternal, or both, toward others, and a female may be maternal or paternal, or both, toward others. These are the acts of mothering and fathering ourselves and others, and the alternative definition in Romantic Dynamics for describing, "courage" - to face fears regardless of how unpleasant we feel - is to say that courage is the act of "fathering ourselves." The act of courage in facing our fears, always leads to having more of the self-esteem called, "confidence," in the same way that the act of assertiveness in getting our own needs met always leads to more of the satisfaction sense, called, "well-being."

And so the sense of happiness needed in order for us to feel friendship or love (or to be friendly and loving), is not provided solely by having fed a hunger and reaching satisfaction (well-being), because we may still feel fear and uncertainty about the world. The happiness we seek in love and romance is also not fully met, simply by facing our fears and winning (confidence), because we may still be hungry and low on resources in life, and therefore not happy.56

To have a complete happiness, a well-rounded love and friendship for another person, and to be fully valued in return, we must all have equal amounts of both well-being and confidence. This is a special key for mastering nearly every emotional situation that comes our way in love and romance, and part of the reason that we view the equation, Self-esteem = Well-being + Confidence as a kind of "E=mc2" of psychology. All emotions, both positive and negative are accounted for in the equation, and a relative imbalance of either, directs us to what it is that we need to change about ourselves and our relationship.

The processes that are emotional, love and friendship based are useful to look at in isolation. However, in Romantic Dynamics, when we talk about the mind with the functional symbolism we term, "reptilian-brained," "mammalian-brained," and "higher-brain." We look at these as being separate in psychological function, and yet they truly interconnect to each other in woven-together ways. As a result, when we see research that shows the relationship between an unconscious, instinctual, "reptilian" function such as imprinting, such as attachment, and more subconscious, emotional, "mammalian" functioning such as self-esteem or happiness, then we find legitimate, scientific, research backing.57

Our development of these functions, begins in what you would expect: infancy.58

The emotions of the mammalian brain sit squarely between the instincts of the unconscious "reptilian brain," and the conscious "higher brain." One crucial way that Romantic Dynamics looks at progress through these "three brains," is to see each one as progressively higher in maturity - from childishness, to adolescence, to full adult maturity.59

The second step of emotional attraction (the fifth step in overall courtship) is Finding Stress in Each Other. This will be the antithesis and threat to our self-esteem, our friendship, our happiness, and our love.

The emotional attraction of the mammalian brain is obviously not just about the positive emotional benefits of love and friendship. They also contain the protection and the antidotes to the negative version of emotions and self-esteem that all couples face. We all know an easy term for the large category here, called, "stress."60

It has been said that, "What doesn't kill you, makes you stronger." Since a couple and the relationship formed by two people amounts to the combination of two separate people's lives, and also a third, "new identity" formed, called "the relationship" itself, it also makes sense that, "What doesn't kill the relationship, makes it stronger."

Stress is definitely this feature of life and romance. And stress has both psychological and biological effects on an individual.61

As a result, by mastering the emotional attraction steps of phase two of courtship, couples really could think of stress as something to be welcomed by them.62

Couples actually shield each other from stress, on top of raising each other's self-esteem as the very definition of love. They do both in love - they raise each other's self-esteem as well as shielding each other from stress with more power than either one can do for themselves.63 If you've ever wondered why it is that friends or couples who endure challenges together, tend to bond to each other even tighter in the relationship, you can probably thank the stress experiences that they encounter, and the mutual empathy that is cultivated there.64

The "winters of our discontent" that they experience, the "cold, cruel world" that they would have lived in, apart, as singles, is ironically what cultivates their growing warmth for each other.65

In this phase of emotional attraction, we all ought to come to the conclusion that emotions are not just emotions to brush by, or to brush under the table. They are crucial, and can either make or break the overall relationship, based on the quality of the friendship, how one is valued, how happy one is, and what aspects of life can help the couple to be happiest, and as free of stress as possible.66

Emotions are not just emotions. They are the very fuel on which romantic relationships run, and their function in romance and friendship are actually predictive of future behaviors and outcomes.67 A far cry from emotions being unreliable, fickle, or not of logical use in planning our lives.

The third step of emotional attraction (sixth overall step of courtship) is Finding Completion in Each Other - which is where we discover the interplay between our personality styles. Nearly anyone can find value of some amount in another person. We can befriend at least to acquaintance levels, nearly anyone who can be friendly back. And nearly any two people can do their best to fight off stress. (It is said that "a common enemy, unites.") But to find someone who is easy to be with, and yet is a great teammate bringing diversity to the partnership - that person is a candidate to go into the whole next phase of courtship - the intellectual attraction of commitment. It is a matter of personality style.

In a media environment where anyone and everyone has a "personality matching system," it is imperative to first define what personality is, and how it differs from the psychoanalytic concept of "character" and character maturity. They are different, for one is a style, and the other is an evolution. In fact, the third and final phase of courtship depends on all the various aspects of character traits, virtues and vices, even as the match of our personality styles forms a bridge to analyzing and building character for partnership.68

In the Social Personality System that we have developed, we start with basic psychological science and the cognitive-behavioral and self-help schools of thought, psychodynamics, and from them, build a system that explains how our personalities cause us to find meaning, communicate it, take action versus thought and strategy, and our social and friendship skills and preferences that can be seen as strengths and weaknesses of the sort that fit like puzzle pieces to the personality of another person - much in line with the concept of the Michelangelo Phenomenon.

In other words, due to the quality of match of our personality styles, we will be better, more masterful or less masterful Michelangelos to each other. The former launches us confidently into the commitment and partnership phase of intellectual attraction.69

INTELLECTUAL ATTRACTION

Crossing the bridge from emotional attraction to intellectual attraction bears some similarities to our first transition, from sexual attraction to emotional attraction, in that there are overlapping features, and an interweaving of the processes of the two phases.

In the case of this transition, there are many more psychological processes that we are familiar with. For example, that communication is of the essence in partnership as well as friendship, and that communication carries both data and emotion (or energy) within it. A similar crossover concept is that of "shared beliefs" - that what we believe in has detail in the data, but the strength of our convictions has everything to do with the amount of positive or negative emotions in the beliefs.

Finally, a third way in which the emotions of the mammalian brain and the ideas of the higher brain are in leagues, is in the form of our Social Personality System, in how it is laid out on a grid composed of two spectra - one for our emotional style" as either more maternal or paternal, and one for our intellectual style as being either more organized and "left-brained" or more disorganized and creative, or "right-brained."

In the end, we will find that the romantic connection between those in intellectual attraction is about mutual success at reaching goals for both members of the couple at this phase. That partnership itself does not require or expect love, nor does it require or expect sex. It is purely the combination and synchrony of the mind power involved. The intention being to successfully reach goals as a team.

Preparing for such a task is a daunting one, since early in this phase, that preparedness would require substantial work on personal growth. Seeing someone grow in front of your eyes, and because of your interactions with them is a miraculous thing, and to know that your own growth happens, in part, because of their intervention is one of the very reasons that we, as homo sapiens, may even relish the prospect of mature romantic love and that last phase - intellectual attraction. It is more than just a feature of personal interest in our own, private goals. Intellectual attraction has equally as its purpose, the notion of constructing a highly functional team of two. As we age, we ought to mutually mature.70

Development is the psychological term for the process of maturing, and we will look at your "personal evolution" from numerous viewpoints which can all work together to explain what maturity is, and why it makes us more prone to success and lasting romance as partners. The works of George Valliant will serve us well, including in his model of what have been called, the "Four Levels of Ego Defense Mechanisms."71

These, originated by Freud, have been reinterpreted by Valliant and others into four categories which reveal what amounts to one's "level of maturity." And if you wonder why this concept of maturity matters, you will be gratified to find out that your maturity level, as well as that of your chosen partner, will directly dictate how successful your committed relationship will be in terms of longevity, and what you both bring to bear in the world. It will also directly correlate with what your resulting personal success is at getting to your purpose in life, and completing your mission in life.

As you may guess, there will be many core features of partnership in which you, and even the most ideal partner you could muster, will differ on, or even come into conflict over. In fact, you ought to be different in many ways - not the least of which is personality style - in order that you both bring diversity to the table, and to the team goals.

Unfortunately, divorce can fairly accurately be predicted now.72 And unfortunately, a perfect, stable, passionate, happy, lasting marriage cannot.

Yet.

Conflict will naturally arise, then, through differences of personality, certainly over differences of maturity level, and or differences in IQ, in culture, in education, economic level, and certainly over the very different, silent, instinctual language of gender differences. In this light, we will need to absolutely bend over backwards to understand each other.73

More and more, there are growing gaps between people in our society, and even between the most well-suited of partners. Sometimes this even extends to there being large age differences between men and women who become partners.74

Never before has maturity mattered so very much, in order for people to get along in marriage and commitment. To those ends, we cannot rest with the nature of the ego defenses as our only measure of maturity, in a world full of opinions of all types about what is mature.

We need facts about maturity, and there are some. Maturity tends to be inversely proportional to one's level of "pathological narcissism," which is a good description of what is immature in behavior. Through this lens, we may see more than clues, but actual ways of measuring maturity through the features of psychology that are present in narcissism, and their absence.

One of the greatest measures rests in the qualities of one's personal boundary skill, and a relative preponderance of "doors" in the boundary as opposed to "holes" or "walls."

Another, well-known to psychoanalysts, is the ability to access Observing Ego, that sense of self-awareness and social awareness that is the antidote to the regrets of immaturity, and a good description of what has been called a "cool" or "classy" person. When it is high, consistently, we are more mature, and when it is lacking, consistently, we are immature.

Other scientists besides Gottman have also laid out detailed analyses of what precise features of our maturity (or its lack) statistically correlate with a successful relationship versus a divorce as the outcome.75 Sometimes these statistics do not explain causation for the demise of the relationship, but they are nonetheless useful in terms of being predictive of what we are after in a relationship, and especially the "how-to" part. What do we physically do or say, in order to have a successful partnership?

Trust must have something to do with this, but so do a host of other emotional, intellectual, and even instinctual features of our identities in romance.76

Our goal in Romantic Dynamics will be to not only work with the statistics of what is likely to give us better relationships, but is an attempt to explain how that comes about - the causation of it all. In a logical, step-by-step way that also carries a great deal of "how-to" power.

Many people wrongfully assume that "commitment" is a terrible thing, a thing to surrender to. And that very well can be, when we select the wrong mate. However, it is our hope that in Romantic Dynamics, you learn to best "matchmake yourself," to the point that commitment to a mate very well suited to you is a better scenario than being single, and actually helps you achieve goals that you otherwise could not have on your own. Commitment does not have to mean sacrifice of the self, the identity, or the life's purpose or mission you were meant for.77 To the contrary - it ought to mean all the more likelihood of not only reaching your own personal goals in life, but discovering new ones which are brought on by the unique features of your partner's psychology.

Some authors have previously considered the use of the triune brain model for looking at romance, such as Harville Hendrix, in his classic, Getting the Love You Want.78 Other more recent revered works include forays into communication styles (which likely have something to do with personality styles), such as The Five Love Languages, by Gary Chapman.79 Like the famed, Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus, by John Gray, these are from the genre called, "self-help books," many of which are written from the personal experience of the author, rather than based in research or scientific theory. And so, as we continue to make our way through the literature, it will help to remember that public popularity does not necessarily correlate with accuracy or even usefulness. (Sometimes the public just wants to hear what it deems to be personally gratifying, rather than what works in practical life, yet might take some work or personal change.)

Yet there are some sources of information that are both easy to understand, and also based in rigorous science and statistical methods that do not merely arise from speculation, opinion, or wishful thinking as to what is true about romantic relationships. The works of Dr John Gottman are a prime example of that.80

More mundane, less celebrated sources may even be among our best, such as the simple observations about "long first marriages" published in the Journal of Mental Health Counseling81

In this last phase of courtship, intellectual attraction, we will be looking to the basic statistics about what is helpful for promoting longevity.82 But there will also be a method to how we weave together everything that we have learned about romance so far.

We will begin the phase with some common sense, and the "step" of intellectual attraction that we call, "Who I Am: Character Maturity." In this first "step," we focus on how an individual readies themselves to be a most fit partner on a team striving toward joint and individual life's goals. And so everything to do with individual personal growth will be covered.

For example, individual character traits that are of the mature variety - consider gratitude as a mature ego defense, or social habit - will be predictive of doing better, in a harmonious relationship that has longevity. 83 When we focus on our own personal psychological fitness for partnership, that is not meant to be a guilt trip, or shame that we self-inflict, but instead, an understanding that part of being in a successful couple will involve championing of our own dreams and aspirations at a meaningful life's purpose.84

An understanding of ourselves will naturally lead to an understanding of our needs, and therefore to the right kind of mate to select. 85 While this will have roots in personality styles, communication and purchasing tendencies and other properties which make us unique, the underlying forces which are universal among people will be just as powerful in determining what mate we select. Such aspects of our identity as the "imprinting processes" of attachment, bonding, identification and finally, "initiation" will also hold sway in a major way when it comes to our neurotic little quirks that lead us to pick who we pick for romance.

We will enter the second step of intellectual attraction with a focus on the "we" as a couple, assuming that both partners have made efforts to become the most mature, team-oriented collaborators that they can be. The step is then, called, "Who We Are: Character Compatibility." The Romantic Dynamics model goes above and beyond what has come before, even in the uses of the triune brain theory. We start to look at how the attachment and bonding processes with our opposite-sex parent, matter in our romantic choices (which Freud once observed in the "Oedipus Complex.") We look at identification with the same-sex parent, and the initiation into their world of tendencies, with the intent to become the next generation with some of the same rules and expectations, but through our own spin on the character nature of that similar parent to ourselves. As a result, we will see four "compatibilities" among couples, emerge:

A compatibility of maturity level is the first. This will make sense to you in looking at partnership as having a goal of harmony in teaming up together for a common goal. This doesn't go well when there is a great gap in maturity level.

Secondly, we tend to do best with someone of similar intelligence or IQ. It won't make sense to partner with a person who doesn't at all get where we are coming from, nor someone who doesn't even understand our life's goals, let alone being someone with who naturally works against what they simply do not understand.

We can naturally, then expect to get in some conflict, and the ways which we use to resolve such conflicts with have great bearing on how long we last.86

We may find ourselves in an "empathic failure," no which our spouse experiences us as not caring about their life's goals and dreams.87

In conflict, we may find ourselves not understanding the language of the other person, misinterpreting it, or twisting it to fit our view of what is true about the world, or about ourselves.88 We must make it our goal to continue to support the identity and expression of the spouse.89 In so doing, we will find that we actually have more similarities with each other, than differences.90

One of the highest character virtues that we will need to cultivate will be that of forgiveness, since we are all, each of us, imperfect.91

In this step, we will have struck upon certain things about our development that we cannot help, and which were not our fault (we had the particular mother and father that we did.) From the same-sex parent, we will have developed a "taste for" or "type" that we look for in a mate, and with character flaws and virutes that are unique to our particular parent. Meanwhile, the same-sex parent whom we identified with so long ago, becomes a beacon that we put out in attracting a mate in kind - that causes other people to find us appealing, not because they randomly seek out our particular flaws and virtues, but out of the similarity between us and their own, opposite-sex parent.

Yet, we are now in the conscious part of the mind, and we can make conscious choices that steer those instinctual, long-ago unconsious choices. For example, we will meet numerous people with similarities of virtue similar to our own opposite-sex parent. And yet we do not have to choose to be with the first one who comes along. Instead, we can sit back and watch who is attracted to us, and who we are attracted to, but we can choose the ones who also have more virtue than vices which we had recognized in our own opposite-sex parent. The same is true of our prospective mate.

In the end, we will choosing the fittest possible partner if we side with choosing those with more virtue than vice, and yet who also do resemble in behavior, our well-loved parent. This will preserve both the passion for the right person for us, and yet also will cultivate the spirit of being able to team up toward prosperous goals. In so doing, we find that we are transformed by the other person, as are they, by us.92

We may, after all this time, actually find deal-breakers and incompatibilities between us. Yes, even now.93 Therefore, our ability to describe ourselves as accurately as possible to the other person in terms of needs, wants, desire, habits, style and all those compatibilities such as our beliefs, our intelligence, and the conveyance of our true maturity level, will pay off if we had started early.94

We will find ourselves naturally fitting into a life's narrative with the other person, and one which feels right, easy, natural, authentic and satisfying.95 To many of us, this will seem almost magical, or of "good luck." In reality, part of it is what we naturally, autonmatically need in a romantic partner, and so of course, that was whom we attracted. Yet another part of this comes from our personal experience, sometimes making the same romantic mistake multiple times until we learn its lessons.

We will, at this point, have proven ourselves to be compatible in several areas to quite a degree, and we will have naturally tested and cultivated four skills of mature romantic partnership: curiosity about the other person, regular communication with them, compromise (not in sacrifice, but in synthesizing together our needs and strengths), ending in execution of our joint actions, and using our joint resources, with collaboration toward life's goals.

These "four commonalities of commitment": Maturity, IQ, Beliefs/Values, and Joint Life's Goals - combined with "the four C's of commitment" - curiosity, communication, compromise, and collaboration - combined, make for "16 master compatibilities of commitment" - which will tie us back to what we inherited, identified with, and learned from our same-sex parent, and what we are attracted to, by attachment, in our opposite-sex parent. This feature of Romantic Dynamics is perhaps, one of the most interesting and targeted technologies of compatibility and romantic assessment that we have developed.

What the 16 compatibilities leads us to is both a way to troubleshoot our relationship, to decide whether to commit for life in the first place, and after we have done so, to always have 16 core items to focus on in building and maintaining the strength and power of our partnership. It is then, that we can be "sure that we're sure" of the person we are with, and can confidently take risks in striving for joint goals in life, together.

We will, at this point, have proven ourselves to be compatible in several areas to quite a degree, and we will have naturally tested and cultivated four skills of mature romantic partnership: curiosity about the other person, communication with them regularly, compromise (not in sacrifice, but in synthesizing together our needs and strengths, ending in execution of our joint actions, and using our joint resources, with collaboration toward those life's goals.

The third and final step of intellectual attraction and partnership will then be called, "Where We Are Going: Joint Life's Goals." It is here that we have truly developed a faith in each other and in the relationship. We are ready for the universals, such as sharing a home, having children, and contributing to the community around us as a couple.96

This is not to say that striving for life's goals is easy. Having a baby is very HARD, no matter how good your compatibility.97

This is true of both our personal life's goals, and the universal joint goals of the couple. The world out there is hard enough, without an incompatibility of the couple itself getting in the way - an "enemy within." Not only are the goals we face, hard to reach, but there will be numerous challenges in the way on top of all this - financial, personal, even heatlh problems.

Even the words we use with each other can cause harm.98 Words can (indirectly) kill. Luckily we have already mastered communication that comes from a previously established, loving place, of friendship.

Which is also why the last step of the last phase of courtship - going for the life's goals together - doesn't end at the end of a line, but doubles back to the beginning, a circle, for maintenance of the relationship. There will always be threats to encounter and adapt to, or fly around as we continue our life's purpose and mission. Even social media and other distractions can get in the way of what we share.99 We can be seduced by virtual worlds, porn, gossip, and all the destructive tools of the "Sisters of Psyche" that so unjustly cast the Eros in a man, as somehow a monster.100

We will find that our friends, both those personal, and those jointly the couple's, will bouy us in rocky seas,101and through it all, we need to remember just those first moments of meeting, the wordless feelings that we had about each other, and what they informed us about in who would become our future mate.102

We will have to come face to face with the ever-present possibility of "growing apart" unless we do this ongoing maintenance.103 And we will only have the constant communication between us to keep us together, remembering the "Michelangelo Phenomenon" - that we "sculpt each other" and can only do so by contact with each other, and the ongoing sharing, consistency, mutuality and positivity of friendship.104

We may even need to learn techniques of "fighting fair," since we are always going to be separate individuals trying to find common ground and common goals.105

We may rely on the feedback of our friends to give us reality testing and ground to walk on in judging our progress, our temprary failures, and our comebacks in romance, knowing that there are seasons of love, and waves of romance to ride through life.106

We must remember that anger has a good place, and need to be expressed, that it is entirely normal to come into conflict, and just as normal, in fact, mature, to become more and more skilled at working the conflicts out.107 It may be a good thing to remember that fighting early in dating reveals a great deal about what is to come, and certainly before becoming engaged or married, hopefully you and your partner have had some very dramatic, blowout fights. They will tell all about the future.108

Often, the fights will be about money or sex, the twin forces of the unconscious, reptilian instincts of desiring each other.109

You've come so very far at this point, but until many cycles of maintenance have occurred, we may still remain weak in our romance, even with great compatibility. Sometimes, life works in a way which does not align with what we want or need, and divorce will be inevitable.110

All living things enjoy the warmth of the sun for awhile, and eventually will die. We must accept that this is the case for our own lives and even our relationships. Married for life, each of us will still, someday part. When that day approaches, we can be ready for it, with peace and tranquility, always curious, always learning.111

Sometimes, it is through one ending that we learn all we need to know about keeping the next beginning alive for much, much longer.112

There is even research about the differences between how relationships end at the non-marital (first or second phase) level versus at the marital, committed (phase three) level.113

Staying in bad relationships affects our health, and the act of getting out of them at least temporarily affects our health.114 We may be wise to let how we sense our health declining in a relationship to spur us to get out.115

Once we reach the consistent, trusting contact that the partnership of intellectual attraction allows, we also may tap into the benefits that are possible - the healing power of love that is lasting and durable.116

We may find that following on the coattails of our good health by virtue of being with a good partner, our financial health improves as well.117 In fact, our overall family now thrives, should we have children, and their minds and bodies are healthy because ours are as well.118 The cycle will continue as our own children attach and bond to us, and are more fit than would otherwise be the case, to someday enter healthy relationships of their own.119 We will have done our homework and prepared for the stress of having had the infant, and now it pays off in their health and progress.120 We have proven something about our own partnership when we have had a child, stayed together, and seen them grow up to be healthy and happy, themselves.121

It is through reaching the end of the steps of courtship, and returning to the beginning once more, that we maintain and strengthen what we've built, that a family grows, and courtship continues all our lives. Someday, we may even become the students of our own children when it comes to love, and someday we may find ourselves needing them more than they need us.122

There are as many ways to opine about the magic of love, the mystery of desire, and the contentment of well-matched partnership, as many ways as there are poets or poems, singers or songs. Music, literature, art, and even film inform us, if not on the hard science of courtship itself, then on what our dreams are for romance. One of the best summations of partnership in romance that I have seen are the words of actress Susan Sarandon, as the wife to Richard Gere's husband in the film, Shall We Dance?

She says that marriage may be a lot of different things, but what is true of it universally, when everything else is boiled away, what does it mean to us, is this: we are witness to each other's lives, like no one else ever could be, (not even our parents.)

We must all remember this as the first, and last thread of our bond, even when things seem to have entirely unraveled. It is the one, remaining good thing about even the worst of the worst dramas of romance we endure. And it is the rock on which we may start over, and build again:

Be curious, and be a good listener, and things will some way, somehow, be alright.

- Driver, J.L. & Gottman, J.M. (2004). Daily marital interactions and positive affect during marital conflict among newlywed couples. Family process, 43 (3), 301-314.

- Feeney, B.C., Lemay, Jr., E.P. (2012). Surviving relationship threats: The role of emotional capital. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Vol 38, Issue 8, pp. 1004 - 1017.

- Walsh, C.M., Neff, L.A., Gleason, M.E.J. (2017). The Role of Emotional Capital During the Early Years of Marriage: Why Everyday Moments Matter. Journal of Family Psychology. 31 (4), 513-519.

- Huston, T.L., Caughlin, J.P., Houts, R.M., Smith, S.E., George, L.J. (2001). The connubial crucible: newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001 Feb; 80 (2),: 237-52.

- Johnson, S. M. and Greenman, P. S. (2006), The path to a secure bond: Emotionally focused couple therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62: 597–609.

- Johnson, S. M. and Whiffen, V. E. (1999), Made to Measure: Adapting Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy to Partners' Attachment Styles. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6: 366–381.

- Hazan C, Shaver, P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987 Mar; 52(3):511-24.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

- Gottman, J.M, & Levenson, R.W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 221-233.

- Johnson, S. M., Hunsley, J., Greenberg, L. and Schindler, D. (1999), Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy: Status and Challenges. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6: 67–79.

- Weiss, R. L. (1980). Strategic behavioral relationship therapy: Toward a model for assessment and intervention. In J.P. Vincent (Ed.), Advances in family intervention, assessment, and theory Vol. 1 (pp. 229-271). Greenwich, CT: JAI Process.

- Wieselquist J., Rusbult, C.E., Foster, C.A., & Agnew, C.R. (1999). Commitment, pro-relationship behavior, and trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77(5):942-66.

- Stafford, L., Dainton, M., & Haas, S. (2000). Measuring routine and strategic relational maintenance: Scale revision, sex versus gender roles, and the prediction of relational characteristics. Communication Monographs, 3, 306–323.

- Egbert, N., & Polk, D. (2006). Speaking the language of relational maintenance: A validity test of Chapman’s (1992) five love languages. Communication Research Reports, 23, 1-8.

- Giedd J.N., Lalonde, F.M., Celano, M.J., et al. (2009) Anatomical Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Typically Developing Children and Adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 48(5):465-470.

- Tierney A.L., Nelson, C.A. (2009). Brain Development and the Role of Experience in the Early Years. Zero to three. 30(2):9-13.

- Hawkins, M. W., Carrère, S. and Gottman, J. M. (2002), Marital Sentiment Override: Does It Influence Couples' Perceptions?. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64: 193–201.

- Notarius, C. I., Benson, P.R., Sloane, D. Vanzetti, N.A., & Hornyak, L.M. (1989). Exploring the interface between perception and behavior: An analysis of marital interaction in distressed and nondistressed couples. Behavioral Assessment, 11, 39-64.

- Babcock, Julia C.; Gottman, John M.; Ryan, Kimberly D.; Gottman, Julie S. (2013). A component analysis of a brief psycho‐educational couples’ workshop: One‐year follow-up results. Journal of Family Therapy, Vol 35(3), 252-280.

- Askenasy, J. & Lehmann, J. (2013) Consciousness, brain, neuroplasticity. Frontiers in Psychology. 4:412.

- Fuchs, E., & Flügge, G. (2014). Adult neuroplasticity: more than 40 years of research. Neural Plasticity.

- Wiebe, S. A., Johnson, S. M., Burgess Moser, M., Dalgleish, T. L., Tasca, G. A. (2017). Predicting follow-up outcomes in emotionally focused couple therapy: The role of change in trust, relationship-specific attachment, and emotional engagement. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43, 213–226.

- Verhofstadt, L.L., Buysse, A., et al. The Role of Cognitive and Affective Empathy in Spouses’ Support Interactions: An Observational Study. Lahvis GP, ed. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0149944.

- Davidson, R.J. (1994b). Asymmetric brain function, affective style, and psychopathology: The role of early experience and plasticity. Development and Psychopathology, 6, 741-758.

- Braxton-Davis, Princess (2010) " The Social Psychology of Love and Attraction," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 14: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: h p://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol14/iss1/2

- Victor Karandashev, Brittany Fata, Change in Physical Attraction in Early Romantic Relationships, Interpersona, 2014, Vol. 8(2), doi:10.5964/ijpr.v8i2.167

- Rebecca Curnalia, Interpersonal Attraction from Insight to Innovation: Applying Communication Theory in our Web 2.0 Lives. Kendall Hunt Pblishing, 2016.

- B. Zilbergeld (personal communication, 1995). Zilbergeld, B. (1999). The new male sexuality. New York: Bantam.

- Tierney AL, Nelson CA. Brain Development and the Role of Experience in the Early Years. Zero to three. 2009;30(2):9-13.

- Beckes L., IJzerman H., & Tops, M. (2015). Toward a radically embodied neuroscience of attachment and relationships. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 9:266.

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995 May; 117(3):497-529.

- Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), pp.759-775.

- Cupach, W. R., & Metts, S. (1995). The role of sexual attitude similarity on romantic heterosexual relationships. Personal Relationships, 2, 287-300.

- Robinson, E. A., & Price, M. G. (1980). Pleasurable behavior in marital interaction: An observational study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 48, 117-118.

- Johnson, S. and Zuccarini, D. (2010), Integrating Sex and Attachment in Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36: 431–445.

- Cupach, W. R., & Metts, S. (1991). Sexuality and communication in close relationships. In K. Mckinney & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Sexuality in close relationships (pp. 93-110). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cupach, W. R., & Comstock, J. (1990). Satisfaction with sexual communication in marriage. Links to sexual satisfaction and dyadic adjustment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 179-186.

- Barbach, L. (1984). For each other: Sharing sexual intimacy. New York: Signet.

- Hertenstein, M.J., Keltner, D., App, B., Bulleit, B.A., & Jaskolka, A.R. (2006). Touch communicates distinct emotions. Emotion. 6(3):528-33.

- Waters SF, Virmani EA, Thompson RA, Meyer S, Raikes HA, Jochem R. Emotion Regulation and Attachment: Unpacking Two Constructs and Their Association. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32(1):37-47.

- Ekman, P. (1984). Expression and the nature of emotion. In K.R. Schere & P. Ekman (Eds.), Approaches to emotion (pp. 319-344). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Drigotas, S. M. (2002), The Michelangelo Phenomenon and Personal Well-Being. Journal of Personality, 70: 59–77.

- The Science of Happiness. (n.d.). Retrieved 2016, from https://www.edx.org/course/science-happiness-uc-berkeleyx-gg101x-5.

- Kahneman D. Objective Happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwartz N, editors. Well-Being: The Foundation of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 3–25.

- Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC. The Neuroscience of Happiness and Pleasure. Social research. 2010;77(2):659-678.

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Gratitude and Well Being: The Benefits of Appreciation. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(11):18-22.

- Grant, Adam M.; Gino, Francesca. A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 98(6), Jun 2010, 946-955.

- Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counted blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:377–389.

- Masood, A.; Mazahir, S. Relational Communication, Emotional Intelligence, and Marital Satisfaction. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology 4:4. June 2015.

- Kahneman D, Deaton A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(38):16489-16493. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011492107.

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Gratitude and Well Being: The Benefits of Appreciation. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(11):18-22.

- Algoe, Sara B.; Fredrickson, Barbara L.; Gable, Shelly L. The social functions of the emotion of gratitude via expression. Emotion, Vol 13(4), Aug 2013, 605-609.

- Verhofstadt L, Devoldre I, Buysse A, et al. The Role of Cognitive and Affective Empathy in Spouses’ Support Interactions: An Observational Study. Lahvis GP, ed. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0149944.

- Davidson, R.J., McEwen, B.S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature neuroscience. 15(5):689-695.

- Frith, U. & Frith, C. The social brain: allowing humans to boldly go where no other species has been. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010 365 165-176; DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0160. Published 24 November 2009.

- The Science of Happiness. (n.d.). Retrieved 2016, from https://www.edx.org/course/science-happiness-uc-berkeleyx-gg101x-5.

- Gianino, A., & Tronick, E.Z. (1988). The mutual regulation model: the infant’s self and interactive regulation and coping and defensive capacities. In T.M. Field, P.M. McCabe, & N. Schneiderman (Eds.), Stress and coping across development (pp. 47-70). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Dawson, G. (1994). Development of emotional expression and emotion regulation in infancy: Contributions of the frontal lobe. In G. Dawson & K.W. Fischer (Eds.), Human behavior and the developing brain (pp. 346-379). New York: Guilford.

- Farley, J.P. & Kim-Spoon, J. The Development of Adolescent Self-Regulation: Reviewing the Role of Parent, Peer, Friend, and Romantic Relationships. Journal of adolescence. 2014;37(4):433-440.

- Pasch, Lauri A.; Bradbury, Thomas N. Social support, conflict, and the development of marital dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol 66(2), Apr 1998, 219-230.

- Axelrod, J., & Reisine, T.D. (1984). Stress hormones: Their interaction and regulation, Science, 224 (4648), 452-459.

- Bruce S. McEwen. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews Published 1 July 2007 Vol. 87 no. 3, 873-904.

- Bruce S. McEwen. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews Published 1 July 2007 Vol. 87 no. 3, 873-904.

- Sened, H., Lavidor, M., Lazarus, G., Bar-Kalifa, E., Rafaeli, E., & Ickes, W. (2017). Empathic Accuracy and Relationship Satisfaction: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Family Psychology.

- Williams, Lisa A.; Bartlett, Monica Y.Warm thanks: Gratitude expression facilitates social affiliation in new relationships via perceived warmth. Emotion, Vol 15(1), Feb 2015, 1-5.

- Levenson, R.W., & Gottman, J.M. (1985). Physiological and affective predictors of change in relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 85-94.

- Carstensen, L. L., Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1995). Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging, 10, 140–149.

- Yang Claire Yang, Courtney Boen, Karen Gerken, Ting Li, Kristen Schorpp, and Kathleen Mullan Harris. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human lifespan PNAS 2016 113 (3) 578-583; published ahead of print January 4, 2016

- Kaska E. Kubacka, CatrinFinkenauer, Caryl E. Rusbult, LoesKeijsers. Maintaining Close Relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Vol 37, Issue 10, pp. 1362 - 1375.

- Vaillant, George E. Aging Well, 2002

- Vaillant, G., Mukamal K. Successful Aging. American Journal of Psychiatry, 2001: 158:839–847

- Buehlman, K., Gottman, J.M. (1996). The oral history interview and the oral history coding system. In J.M. Gottman (Ed.), What predicts divorce: The measures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Acitelli L.K., Douvan E, Veroff J. Perceptions of conflict in the first year of marriage: How important are similarity and understanding? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10:5–19.

- Seider B.H., Hirschberger G., Nelson K.L., Levenson R.W. (2009). We can work it out: age differences in relational pronouns, physiology, and behavior in marital conflict. The Journal of Psychology and Aging. 2009 Sept. 24 (3), 604-13.

- Gottman, J.M.; Krokoff, L.J. Marital interaction and satisfaction: A longitudinal view. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol 57(1), Feb 1989, 47-52.

- Wieselquist J., Rusbult, C.E., Foster, C.A., & Agnew, C.R. (1999). Commitment, pro-relationship behavior, and trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77(5):942-66.

- Stanley S.M., Whitton S.W., Sadberry, S.L., Clements M.L., Markman, H.J. Sacrifice as a predictor of marital outcomes. Family Process. 2006 Sep; 45(3):289-303.

- Hendrix, H. (1990). Getting the love you want: A guide for couples. New York: Perennial Library.

- Chapman, Gary. The Five Love Languages, Northfield Publishing; Reprint edition, January 1, 2015.

- Babcock, Julia C.; Gottman, John M.; Ryan, Kimberly D.; Gottman, Julie S. (2013). A component analysis of a brief psycho‐educational couples’ workshop: One‐year follow-up results. Journal of Family Therapy, Vol 35(3), 252-280.

- Fenell, D. Characteristics of long-term first marriages. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 1993;15:446–460.

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: a review of theory, method, and research. Psychol Bull. 1995 Jul; 118(1):3-34.

- Gordon, Amie M.; Impett, Emily A.; Kogan, Aleksandr; Oveis, Christopher; Keltner, Dacher. To have and to hold: Gratitude promotes relationship maintenance in intimate bonds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 103(2), Aug 2012, 257-274.

- Burnett, W., & Evans, D. J. (2016). Designing your life: How to build a well-lived, joyful life.

- Sandra C. Matz, Joe J. Gladstone, David Stillwell (2016). Money Buys Happiness When Spending Fits Our Personality. Psychological Science. Vol 27, Issue 5, pp. 715 - 725. April 07, 2016.

- Yu, T., Pettit, G,S., Lansford, J.E., Dodge, K.A., Bates, J.E. The Interactive Effects of Marital Conflict and Divorce on Parent-Adult Children’s Relationships. Journal of marriage and the family. 2010;72(2):282-292.

- Winczewski, L.A., Bowen, J.D., & Collins, N.L. (2016). Is Empathic Accuracy Enough to Facilitate Responsive Behavior in Dyadic Interaction? Distinguishing Ability From Motivation. Psychological Science. 27(3):394-404.

- Kominsky, J.F., Keil, F.C. (2014). Overestimation of Knowledge About Word Meanings: The “Misplaced Meaning” Effect. Cognitive science. 38(8):1604-1633.

- Verhofstadt, L.L., Buysse, A., Ickes, W., Davis, M, &Devoldre, I. (2008). Support provision in marriage: The role of emotional similarity and empathic accuracy. Emotion, Vol 8(6), Dec 2008, 792-802.

- Acitelli L.K., Douvan E, Veroff J. Perceptions of conflict in the first year of marriage: How important are similarity and understanding? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10:5–19.

- Wieselquist, J. Interpersonal forgiveness, trust, and the investment model of commitment Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. Vol 26, Issue 4, pp. 531 - 548.

- Fincham, F.D., Stanley, S.M., Beach, S.R.H. (2007). Transformative processes in marriage: An analysis of emerging trends. Journal of marriage and the family. 69(2):275-292.

- Birditt, K.S., Brown, E., Orbuch, T.L., McIlvane, J.M. Marital Conflict Behaviors and Implications for Divorce over 16 Years. Journal of marriage and the family. 2010;72(5):1188-1204.

- Gottman, J.M., Coan, J., Carrere, S., Swanson, C. Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:5–22.

- Buehlman, K., Gottman, J. M., & Katz, L., (1992). How a couple views their past predicts their future: Predicting divorce from an oral history interview. Journal of Family Psychology, 5 (3-4), 295-318.

- Buehlman, K., Gottman, J. M., & Katz, L., (1992). How a couple views their past predicts their future: Predicting divorce from an oral history interview. Journal of Family Psychology, 5 (3-4), 295-318.

- Shapiro, Alyson Fearnley; Gottman, John M.; Carrére, Sybil (2000). The baby and the marriage: Identifying factors that buffer against decline in marital satisfaction after the first baby arrives. Journal of Family Psychology, Vol 14(1), 59-70.

- Graham, J.E., Glaser, R., Loving, T.J., Malarkey, W.B., Stowell, J.R., Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.. Cognitive Word Use During Marital Conflict and Increases in Proinflammatory Cytokines. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2009;28(5):621-630.

- Lapierre, Matthew A.; Lewis, Meleah N. Should It Stay or Should It Go Now? Smartphones and Relational Health. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, Apr 21 , 2016

- Dew, J., & Tulane, S. (2015). The association between time spent using entertainment media and marital quality in a contemporary dyadic national sample. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36, 621–632.

- Pasch, Lauri A.; Bradbury, Thomas N. Social support, conflict, and the development of marital dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol 66(2), Apr 1998, 219-230.

- Carrere, S., & Gottman, J. M. (1999). Predicting divorce among newlyweds from the first three minutes of a marital conflict discussion. Family Process, 38(3), 293-301.

- Gottman J.M., Levenson, R.W. A two-factor model for predicting when a couple will divorce: exploratory analyses using 14-year longitudinal data. Family Process. 41: 83-96.

- Gottman, J.M., Coan, J., Carrere, S., Swanson, C. Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:5–22.

- Gottman, J.M., (1993). The roles of conflict engagement, escalation or avoidance in marital interaction: A longitudinal view of five types of couples. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 61 (1), 6-15.

- Matthews LS, Wickrama KAS, Conger RD. Predicting marital instability from spouse and observer reports of marital interaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:641–655.

- Fincham, F.D. Marital conflict: Correlates, structure, and context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:23–27.

- Carrere, S., & Gottman, J. M. (1999). Predicting divorce among newlyweds from the first three minutes of a marital conflict discussion. Family Process, 38(3), 293-301.

- Papp LM, Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC. For Richer, for Poorer: Money as a Topic of Marital Conflict in the Home. Family relations. 2009;58(1):91-103.

- Gottman J.M., Levenson, R.W. A two-factor model for predicting when a couple will divorce: exploratory analyses using 14-year longitudinal data. Family Process. 41: 83-96.

- Gottman, J.M. (1993). A theory of marital dissolution and stability. Journal of Family Psychology, 7 (1), 57-75.

- Gottman, J. M. and Levenson, R. W. (1999), How Stable Is Marital Interaction Over Time?. Family Process, 38: 159–165.

- Cupach, W. R., & Metts, S. (1986). Accounts of relational dissolution: A comparison of marital and non-marital relationships. Communication Monographs, 53, 311-334.

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K., Loving, T.J., Stowell, J.R., Malarkey, W. B., Lemeshow, S., Dickinson, S.L., & Glaser, R. (2005). Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1377-1384.

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.k., Bane, C., Glaser, R., & Malarkey, W.B. (2003). Love, marriage, and divorce: Newlyweds’ stress hormones foreshadow relationship changes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 176-188.

- Grewen, K.M., Anderson, B.J., Girdler, S.S., & Light, K.C. (2003). Warm partner contact is related to lower cardiovascular reactivity. Behavioral Medicine. 29(3):123-30.

- Dew, J., Britt, S. and Huston, S. (2012), Examining the Relationship Between Financial Issues and Divorce. Family Relations, 61: 615–628.

- Doherty, W.J. (1997). The intentional family: How to build family ties in our modern world. New York: Perseus Books.

- Fiese, B. (1997). Family context in pediatric psychology from a transactional perspective: Family rituals and stories as examples. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22, 183-196.

- Shapiro, Alyson Fearnley; Gottman, John M.; Carrére, Sybil (2000). The baby and the marriage: Identifying factors that buffer against decline in marital satisfaction after the first baby arrives. Journal of Family Psychology, Vol 14(1), 59-70.

- Belsky, J. & Kelly, J. (1994). The transition to parenthood: How a first child changes a marriage, why some couples grow closer and others apart. New York: Dell.

- Cowan, C.P., & Cowan, P.A., Heming, G., & Miller, N.B. (1991). Becoming a family: marriage, parenting, and child development. In P.A. Cowan & M. Hetherington (Eds.), Family Transitions. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.